Geometries of the Sword

Swordsmanship was once considered a Hermetic discipline, governed by the laws of geometry and proportion. Can it give rise to a new form of martial art?

Intro

This article was written by John Michael Greer and originally published in Gnosis magazine’s summer 1996 issue #40. The article remains copyrite of John Michael Greer and is hosted on our website by his request. No part may be published in any medium in whole or part without Mr. Greer’s express permission.

Please note that this article was published in 1996. At this time information available on historic swordplay was very limited. The research of Mr. Greer and of the Historic Fencing Community as a whole has advanced far beyond what it was in 1996. The availability of new research and translations has advanced the community a very long ways and it still has far to go. Nevertheless this article started the entire phenomenon of modern enthusiasm into the work of Gerard Thibault. Mr. Richardson had already been looking for information on Thibault and Destreza based on information found in the writings of Arthur Wise and Edgarton Castle when he was handed a copy of this magazine, it is this article which prompted Jeff Richardson to contact Mr. Greer upon discovering his self published translation of the first 8 chapters. Those self published first 8 chapters were in fact likely the first published english translation of any material on Destreza. The resulting friendship spurred the research of Jeff Richardson into this system and was the impetus that led to the 2001 Destreza workshop in Ashland Oregon.

With the encouragement of Mr. Richardson, Mr. Greer would finish his translation of Thibault’s book and with his help be connected to Chivalry Bookshelf to see it’s first printing. A book release party, lecture, and seminar would be held in Medford Oregon at Barnes and Noble and the Medford Elks Lodge in 2006. A second printing would become available from AEON Books in 2017 and is available here. #CommissionsEarned

In an effort to update this article new footnotes have been added. The numbered footnotes are from the original article. Alphabetical footnotes have been added by Mr. Richardson to bring things more up to date with current research.

The Article

Much of an American generation’s first encounter with the concept of esoteric spirituality came through the odd medium of Kwai Chang Caine, the half American Shaolin monk of the TV show “Kung Fu.” Behind his wanderings through the Old West lay the flashback images of a Chinese temple where masters taught the secrets of the universe along with those of flying side kicks.

The latter, of course, were the immediate source of interest to my friends and me in the early ‘70s, but part of Caine’s attractiveness was that he wasn’t just a martial artist. He could treat wounds, play the flute, meditate, dispense snippets of fortune-cookie philosophy, walk across rice paper without leaving a footprint, and nonviolently pound the stuffing out of a dozen cowboy-hatted heavies without working up a sweat. The man was a human Swiss Army knife, and it was a truism of the series that any garden variety Shaolin monk was equally omnicompetent.

Television Is television, of course, and plenty of the things that went into “Kung Fu” came straight from Never Never Land. (The Shaolin Temple was destroyed a couple of centuries before Caine would have had the chance to study there, for one thing.) At the same time, the image of the esotericist as master of many trades is not all that inaccurate. Many religious traditions have a wide array of auxiliary arts – systems of art and craft which don’t bear directly on the primary work of spirituality, but which have roles, sometimes important ones, in the broader structure of the tradition. A trained practitioner of one of these traditions is likely to have at least a nodding acquaintance with many of these arts.

The development of these auxiliary arts is particularly noticeable in Asian cultures, where large portions of the history of art, architecture, music, literature, medicine, and other disciplines revolve around the development of different monastic orders and religious sects. A properly trained Taoist priest in the modern period, for example, has studied not only philosophy, meditative practice, and ritual, but also calligraphy, music, landscape design, divination, and armed and unarmed combat.(1) In the Western world, much the same thing was once true in monastic circles: auxiliary arts ranging from Gregorian chant to brandy making, to say nothing of more esoteric practices such as the Art of Memory, were at one time common attainments of Catholic monks.

The student of the Hermetic tradition, on the other hand, has fewer options. At present, besides the almost forgotten traditions of lodge architecture and ritual art, there’s a certain amount of literature and art than can be called Hermetic, as well as a fairly large legacy of often dubious medicine. For someone raised on Kwai Chang Caine, these are pretty slim pickings.

Still, the modern Hermetic tradition is shaking off 300 years of living in survival mode, when only the most crucial materials could be preserved in the face of almost universal indifference. At lest for now, the survival of the tradition’s basic practices and teachings seems secure, and the question of auxiliary arts may well be worth opening again. Some of these, of course, will be freshly invented, but there’s also a case to be made for reviving arts that were part of the tradition at an earlier time. The Renaissance, when Hermetic ideas and insights had perhaps their widest circulation in history, is one obvious place to look.

One place within Renaissance culture that may be less than obvious, but which contains some unexplored possibilities for the Hermetic tradition, is to be found in the arts of the sword. There, in the pages of a handful of early fencing manuals, can be traced the origin and flowering of a school of fencing based on Pythagoean geometry and Neoplatonic philosophy – a full-scale Hermetic martial Art.

- - - -

In the year 1553, the press of Antonio Blado, stampadore apostolico to Pope Julious III in Rome, issued a new book on swordsmanship by one Camillo Agrippa. This book, A Tractate of the Science of Arms, with a Philosophical Dialogue, provides the first definite date to a revolution then under way in the arts of combat in Europe.

For well over a thousand years before that time, both the form and use of the sword in the Western world had remained all but unchanged; the only real difference between a spatha of the barbarian invasions and a broadsword of the time of Henry VIII was in the methods of forging and the quality of the metal. Modern historians of fencing tend to treat the swords of these periods as if they were vaguely sharpened steel clubs, which is unfair: the broadswords of the Middle Ages were superbly crafted instruments, and they retained the traditional shape because it worked, with ghastly efficiency. A solid blow from a well-made broadsword can cut a human body in half.(A) Pick up a broadsword and there’s no question of how it’s meant to be used. Sweeping cuts from the shoulder, backed by the momentum of the whole body, gave it the power to drive past shields and batter through armor.(B) The motions involved follow the natural motions of the human body, just like the round “haymaker” punches thrown by untrained fighters. Skill had a definite role in broadsword combat – another point that historians of fencing have tended to ignore – but strength, endurance, and raw courage were the paramount virtues in battle. The romances that were the favorite reading of the feudal warrior aristocracy celebrate mighty blows with the sword, not clever ones.

The new swordsmanship pioneered by Camillo Agrippa took a different approach. Agrippa himself was an architect, engineer, and mathematician, famous in his lifetime for erecting the great obelisk in the center of the piazza of St. Peter in Rome. He was also a close friend of Michaelangelo, who provided illustrations for his book.(C) He turned to questions of swordsmanship with the same spirit of inquiry that marked Renaissance culture as a whole.

Like so many other advances of that age, Agrippa’s new swordsmanship had roots in one of the rediscovered treasures of classical culture. The recovery of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio’s Ten Books on Architecture, written around the beginning of the Common Era, had sparked a revolution in thought that did not stop at the limits of the architect’s craft. To Vitruvius, geometry and proportion provided the master key to all forms of design; the best and most perfect proportions were those of the human body, worked out and applied according to the rules of geometry.(3) This same fusion of geometrical abstraction with the solid realities of the human form can be applied to combat as well, and Vitruvian ideas, which played a similar role in other facets of Renaissance culture, were central to Agrippa’s new art of fencing.

The propositions of Euclid may seem far removed from the rough-and-tumble of combat, but there is (no pun intended) a point to the connection. The sword is perhaps the most geometrical of all weapons, a straight line moved through space to intersect another line or penetrate the surface of an opponent’s body; each movement of a sword in combat is an arc or a line. Euclid had demonstrated centuries earlier that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, and Agrippa’s most important insight was that this idea should be applied to swordsmanship.

This involved a break with tradition on a larger scale than a first glance may show. The round motions of a cut, as mentioned above, follow the natural movements of the body, but to thrust in a straight line requires practice and careful coordination. At the same time, the shorter distance needed for a thrust to reach its target makes it quicker than a cut, just as the straight punch of a boxer will hit while a haymaker is still swinging through the air. The shift from cutting to thrusting thus put a premium on quickness, dexterity, and training rather than on simple force, and changed the entire context of swordsmanship.

In Agrippa’s manual, following the principles of geometry, cuts with the sword’s edge took a secondary role to thrusts with the sword’s point. The natural proportions and positions of the human body defined a new and more mobile stance, and new guards (the positions in which the sword is held before beginning an attack or parry) kept the sword’s point always directed at the opponent, ready to thrust across the shortest possible space. The result was a new and extremely effective kind of swordplay, one that soon came to dominate the arts of combat across Europe. The Italian style of fencing, as it came to be called, was the ancestor of most subsequent styles of swordplay as well as of modern sport fencing.

A new kind of sword designed to suit this style, known as the rapier, followed quickly. Long and slender – many had well over a yard of blade alone – it was double-edged and had a swirl of metal bars about the hilt to ward off disabling attacks on the wrist. A precise weapon, designed to skewer rather than dismember, it was to the broadsword roughly what a hunting rifle is to a military assault weapon. The comparison is a precise one: the swords and swordsmanship used in warfare continued to rely on the cutting edge for another 350 years, until modern firepower rendered the last survivals of the sword utterly obsolete at the beginning of World War I.

- - - -

The cultural milieu of the Renaissance gave philosophical, religious, and esoteric connections to geometry that allowed Agrippa’s practical insights to be developed in unexpected ways. The classical writing recovered by Renaissance humanists included most of the surviving works of Pythagorean and Neoplatonic philosophy, in which mathematical symbolism was wedded to mystical practice. These sparked a major revival of the esoteric geometry and numerology of Pythagoras and his successors, a revival central to much of Renaissance thought.(4)

The role of number mysticism and geometry in Renaissance esotericism is hard to overstate. Marsilio Ficino, whose fifteenth-century translations of Plato and the Hermetic writings jump-started the magical revival, was familiar with the new Vitruvian architecture and used its principles of proportion in his own esoteric writings. His younger contemporary Giovanni Pico de Mirandola, whose Nine Hundred Conclusions represent the first public manifesto of the new esotericism, devoted 72 of the Conclusions to mathematics and geometry. Many of the important publications of Renaissance esotericism, from the De Harmonia Mundi of Francesco Giorgi (1525) to the encyclopedic works of Robert Fludd a century later, draw extensively on Vitruvian concepts, using proportion and geometry as a key to the nature of the physical and nonphysical worlds.(5)

Nor was this borrowing a one-way affair. These magical traditions of geometry were incorporated into Renaissance art and architecture so thoroughly that an enormous range of Renaissance buildings show the hallmarks of Pythagorean thought; it can be said without much exaggeration that to the Renaissance architect, geometry was Pythagorean.(6) The revolution in swordsmanship set in motion by Camillo Agrippa was a natural subject for the same process. Though Agrippa’s own work made no reference to the mystical implications of geometry, the fusion of the Vitruvian approach and the art of fencing opened the door to much more extensive developments along these lines.

- - - -

The year 1582 saw the publication of another major work on swordsmanship. On the Philosophy of Arms and Their Dexterous Handling, and on Christian Attack and Defense by Jeronimo de Carranza(7) was in its own way as revolutionary as Agrippa’s work. Like its predecessor, it applied geometry to the subject of fencing, but it did so on a much wider scale.

Carranza’s approach to swordsmanship, the foundation of what became the Spanish style of fencing, combined the linear thrusts of Agrippa with circular footwork. In training, a circle would be traced out on the ground, its diameter equal to the maximum length of an effective thrust. Standing at opposite edges of this circle, the combatants were just out of range of each other. Any movement across or around the circle offered the possibility of attack; Carranza traced out these movements and their possible counters in geometrical terms as relationships in space.

As the Spanish school developed, the subtlety and complexity of these analyses increased to a remarkable degree. In the writings of Luis Pacheco de Narvaez, Carranza’s greatest pupil and the most famous of Spain’s fencing masters, the responses to a given movement of the adversary depend not only on the movement itself, but on such things as the adversary’s balance of humors – the four principles, identified with blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile, that were central to Renaissance medicine and psychology – and subtle variations in the quality of the motion.

To modern eyes used to the flashy movements and sport-fencing techniques of Errol Flynn and the various Three Musketeers movies, a duel fought in the Spanish style would be an odd spectacle. The combatants stood straight, feet close together and knees only slightly bent, facing each other side-on with right arms and swords extended. Their feet were inconstant motion as they circled left and right, seeking an opening for a sudden thrust with the arm – the lunge had not yet been invented – or sidestepping an attack.

Modern historians of fencing have had a hard time believing that this manner of swordplay could have been of any use at all.(8) Nonetheless Spanish fencers had a reputation as lethal duelists throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when this school was at its height. Their reputation carried weight even in cultural backwaters such as England, where Ben Jonson’s Captain Bobadil in Every Man in His Humour talks constantly of the great Carranza. Even the stolid English master-of-arms George Silver, defender of the old broadsword, whose Paradoxes of Defence (1599) is one long diatribe against the “Italianated fight” then being imported into England, grudgingly admitted the effectiveness of the Spanish style of fencing.(9)

To what extent was this extraordinary system shaped by the Pythagorean traditions of geometry we’ve examined? It’s difficult to tell; Spain was as strongly influenced by the esoteric revival of the Renaissance as any European country, but the presence of the Inquisition made Spanish Hermeticists more than usually concerned with staying out of sight. There is, however, one piece of evidence worth considering: the one book on the Spanish style that was written and published outside of Spain.

That book is an astonishing document, the most elaborate work on swordsmanship ever printed as well as one of the most lavishly produced books of an age in which printing often counted among the fine arts. It also, and more significantly, marks the furthest extension of Agrippa’s geometrical approach to fencing, an extension that went beyond the published works of Carranza and Pacheco de Narvaez into an explicitly Pythagorean geometry of the sword.

Gerard Thibault, the author of this work, was a true man of the Renaissance: like Agrippa, an architect steeped in the Vitruvian tradition, but also a noted painter and physician as well as a first-rate swordsman of the Spanish style. In 1611 he took first prize in a fencing competition in Antwerp, competing against the acknowledged Dutch masters of the art, and went on to demonstrate his skill before Prince Maurice of Nassau in a celebrated exhibition lasting several days.(D) He then set out to produce a definitive manual on fencing. L’Academie de L’Espee, produced with the support of the King of France, the holy Roman Emperor, and an array of lesser luminaries, and illustrated by some of the best engravers of the period, took fifteen years just to print, and was finally published a year after the author’s death in 1629.(10)

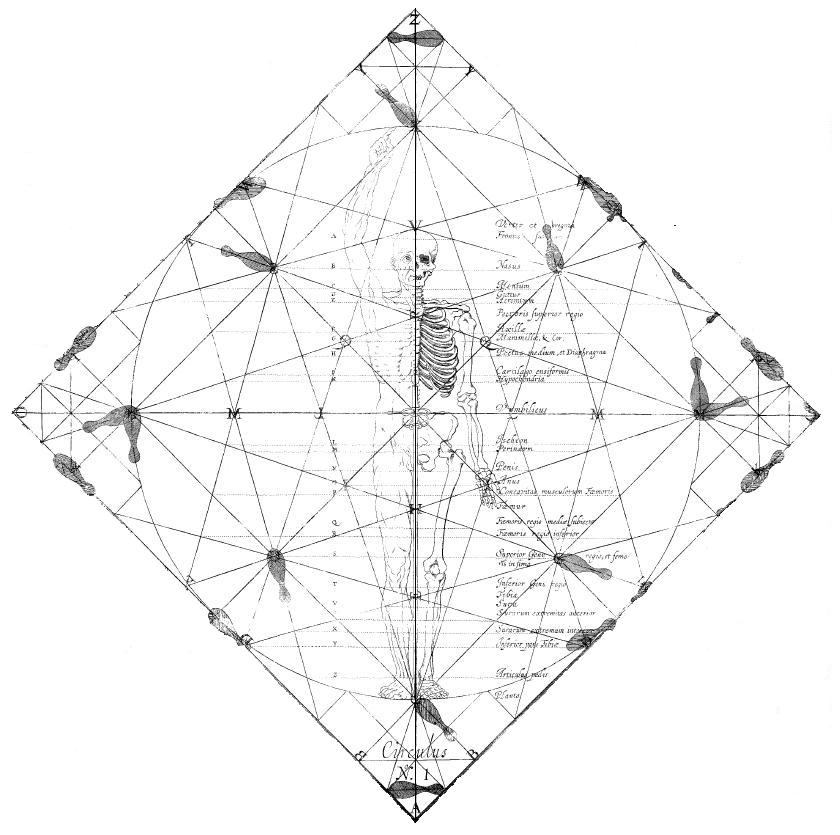

To Thibault, the true art of fencing was founded squarely and explicitly on the geometrical philosophy of Renaissance Pythagoreanism. The human body is a microcosm, a perfect reflection of the universe in its physical and spiritual aspects alike, in its proportions, its “Number, Measure, and Weights,” it contains the harmony of the four elements and the seven planets. So too the positions and movements of fencing and the length of the sword must all be exactly derived from the proportions of the fencer’s body in order to be harmonious and effective. Plato and Pythagoras, as well as Vitruvius, are brought into the discussion, along with references to the measurements of Noah’s Ark and the Temple of Solomon – themselves derived from the mystical proportions of the human body.(11)

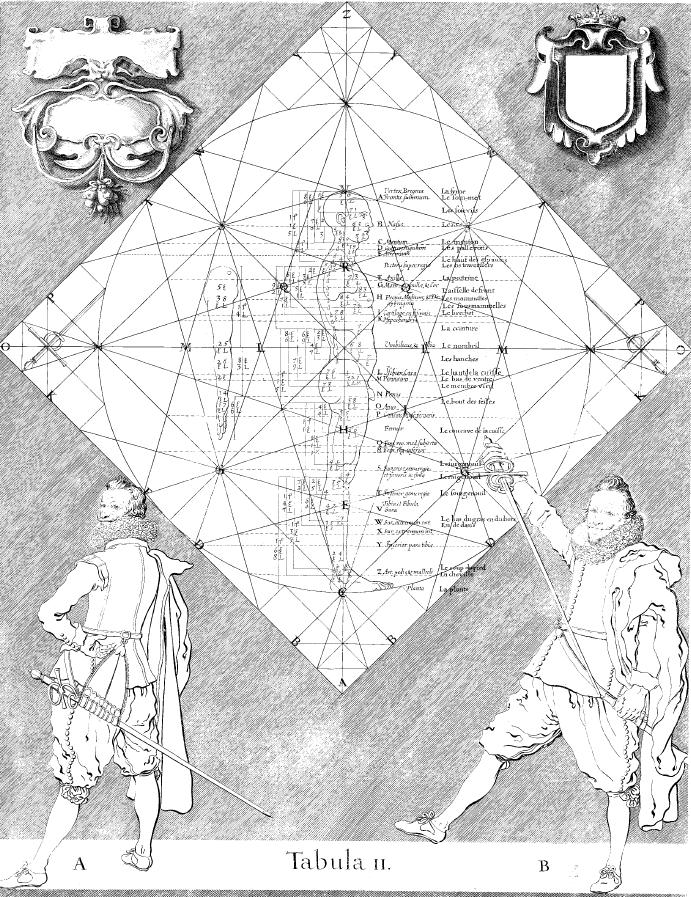

These same proportions define the complex pattern which, according to Thibault, governs footwork in combat (see diagram). The circle of the Spanish school, its diameter redefined as the length of the human body from the feet to the highest reach of a hand above the head, is here inscribed in square. A second square is inscribed within the circle, a set of diameters drawn across it, and a whole series of chords and additional lines defined by these are then drawn in. Every measurement of the diagram is related directly to some part of the body’s dimensions, in a development of Vitruvian theories of proportion as complex as anything attempted in that age.(12)

Based on the proportions of the human body, this diagram from Thibault’s Academie de L’Espee defines the footwork used in fencing in the round. In training, it was drawn on the ground of the practice area, using the rapier itself – proportioned to the body of the swordsman – as compass and pen.

In the training hall, the two combatants stood on opposite sides of a circle and moved from point to point around it as they fought. Just as in the Spanish school, a correct move kept the fencer safe from assault; an incorrect one left him open to a thrust or cut. Thibault’s contention was that a proper mastery of these geometries, not strength or quickness, was the key to survival in the lethal environment of rapier fencing. In the best Neoplatonic style, the realm of ideas was held to master that of space and time.

In its philosophical basis, as well as the scale and lavishness of its presentation, L’Academie de L’Espee invites comparison with the works of Thibault’s contemporary, the great Hermetic encyclopedist Robert Fludd.(13) Fludd’s ambitious attempts to bring all human knowledge into a Hermetically based synthesis derive from the same tradition, and show the same striving for a global view of the cosmos, as Thibault’s work demonstrates in a less universal context. Both Fludd and Thibault also centered their work on the Vitruvian geometries and proportions of the Renaissance esoteric tradition, but used them as the basis for practical arts in a fusion of spirituality and craft that offers important lessons to modern Hermeticists.(14)

In the mainstream of Western culture, though, these works went into eclipse. The Vitruvian swordplay of Thibault was treated as a useless irrelevancy by later fencers, just as Fludd’s philosophy became an object of scorn to the banner-bearers of the Enlightenment.

- - - -

Thibault’s L’Academie de L’Espee is fascinating as a glimpse into one of the less obvious applications of Renaissance Hermetic thought. It may, however, have a more direct use for the modern Hermeticist. Thibault’s work is thorough, to say the least, and can be supplemented by the even more extensive works of the Spanish masters from which his system derives. It’s by no means inconceivable that these could be used to resurrect Thibault’s way of swordsmanship as a Western esoteric martial art.

What would be the advantages of such a project? Issues of self-defense, which usually come up first when martal arts are discussed, are of minor importance here; the rapier isn’t really a suitable means of self-protection on the streets of a modern city. What Thibault’s art of the sword does offer is a physical movement discipline with close links to Hermetic philosophy and practice, something in very short supply in Western esotericism. Martial arts in other spiritual traditions have proven themselves as potent teaching tools, allowing the sometimes abstract insights of philosophy to be grounded in the most material levels of experience.

The revival of these geometries of the sword would require a substantial amount of work and would probably need to begin from a solid foundation of experience in surviving traditions of swordsmanship or other combat arts – a better foundation, certainly, than the present author has gained so far. Still, it offers some intriguing possibilities, and it may be that the time will soon arrive for this auxiliary art of the Hermetic tradition to play a part in the further growth of Western esotericism.

Footnotes

A This may be an exaggeration, but the power of an early period sword is undeniable.

B Cuts were in fact largely delivered by the elbow and an articulation of the wrist, supported by proper body dynamics. While a sword might batter through armor, it was not it’s primary purpose, this is why maces and pole weapons existed.

C These facts come from early published works long used as the standards by the research community. Edgarton Castles work which was repeated by Weiser in “Art and History of Personal Combat”. In fact Architecture historians prove that while Agrippa certainly wrote a text on how to move the obelisk – so did many other writers. Agrippa was not however the architect/engineer in charge of that project. Likewise other than a proximity of locations and a common sponsor in the Medici family, the two men were at different points in their lives and careers and there is no proof that they actually knew each other. Combined with the style of the artwork it seems unlikely that Michaelangelo contributed the illustrations.

D Based on Fontaine de Verwey’s description, These events were described in various panegyrics, by Dirck van Sterbergen and others, in Thibault's album amicorum. Thibault In about 1611 presented himself and his system to the Dutch Fencing Masters assembled at Rotterdam. Here he demonstrated his new rules and took away the prize. He was then invited to the court of Prince Maurice to repeat the display. The Prince attended the demonstrations which lasted for several days and in which several of his officers took part. Thibault received recognition from Maurice's own hands. We believe that Mr. de Verwey misunderstood the documents he was reading and that the tournament was likely Thibault being invited to play his fencing masters prize. More research is needed.

___________________________

1. See, for example, Michael Saso, The Teachings of Taoist Master Chuang (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1978).

2. Camillo Agrippa, Trattato di Scientia d’Armi, con un dialogo di filosofia (Rome: Antonio Blado, 1553).

3. Vitruvius, The Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Morris Hicky Morgan (New York: Dover, 1960), pp. 72-75

4. See Frances Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) for this tradition generally.

5. Frances Yates, Theatre of the World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969) studies these developments of the Vitruvian tradition in detail.

6. See Yates, Theatre of the World; René Taylor, “Architecture and Magic,” in D. Frazer, H. Hibbard, and M.J. Lewine, Essays in the History of Architecture Presented to Rudolf Wittkower (London: Phaidon, 1967), pp. 81-109; and G.L. Hersey, Pythagorean Palaces: Magic and Architecture in the Italian Renaissance (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1976).

7. Jeronimo de Carranza, De la Filosofia de las Armas y de su Destreza, y de la Agresion y la Defension Christiana (Lisbon: n.p., 1582)

8. See, for example, Egerton Castle, Schools and Masters of Fence (York, Pa.: Shumway, 1969), pp. 67-73

9. Qouted in Castle, pp. 92-93. Silver’s work is included in full in James L. Jackson, ed., Three Elizabethan Fencing Manuals (Paterson, N.J.: Scholars Facsimiles & Reprints, 1972).

10. Gerard Thibault, L’Academie de L’Espee (Leiden: Elzevier, 1628 [1630]). See also H. de la fontaine de Verwey, “Gerard Thibault and His L’Academie de L’Espee,” in Quaerendo, vol. 8 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1978).

11. See Joy Hancox, The Byrom Collection (London: Jonathan Cape, 1992), pp. 204-205, where the introduction of Thibault’s work is summarized.

12. Compare the plate from L’Academie de L’Espee reproduced in Hancox, p. 206, with plates from Robert Fludd’s works in Joscelyn Godwin, Robert Fludd (Boulder, Colo.: shambhala, 1979), especially pp. 47, 51, and 72.

13. For Fludd, see Godwin, as well as William H. Huffman, Robert Fludd: Essential Readings (London: Aquarian, 1992).

14. This group is the principal subject of Hancox’s book, to which I am indebted for my first introduction to Gerard Thibault.